Tim Bradner: NGP file photo by Dave Harbour

Petroleum News Update by Tim Bradner: “The exodus of experienced personnel from the department has now become a concern within industry and the state’s business community.”

Alaska Journal of Commerce by Tim Bradner: “ConocoPhillips and Alaska’s state-owned gas corporation, Alaska Gasline Development Corp., say they are negotiating on a joint-venture organization to market North Slope natural gas as LNG.”

Ak-Headlamp. Following last week’s Prudhoe Bay plan of development announcement and subsequent tension between the state and the big three producers, John Hendrix (NGP file photo), chief oil and gas advisor, urged all parties to look for more alignment

Ak-Headlamp. Following last week’s Prudhoe Bay plan of development announcement and subsequent tension between the state and the big three producers, John Hendrix (NGP file photo), chief oil and gas advisor, urged all parties to look for more alignment

Alaska Public Media’s 5 Part Gasline Series

PART I: Video: Forty years of Alaska’s failed gas line plans

Since the 1970’s Alaskan leaders have dreamed of building a gas pipeline from the North Slope. There have been presidential proclamations, congressional hearings and lots of backroom deals, but no project has come close to breaking ground. This week, in the series Pipeline Promises, Alaska’s Energy Desk is taking a look at that history- asking why the project has failed again and again, and whether it may still have a chance.

PART II. The 1970s were a crazy time in Alaska. The state was young and along with that adolescence came its first infatuation, oil. Prudhoe Bay was discovered in 1968 and it changed everything. It was North America’s largest oil field.

But Alaska wanted more, and even as the behemoth Trans-Alaska Pipeline System was being built, several companies were pursuing natural gas pipeline projects to bring North Slope gas to market.

Bill White, a pipeline historian and former journalist, takes reporter Rashah McChesney on a tour of Anchorage that includes the important sites in the state’s long romance with a gas line.

PART III. Man on a mission: Gov. Walker and the gas line

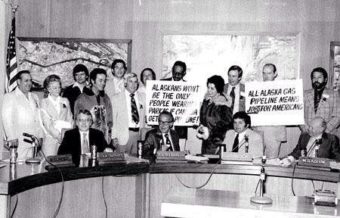

In 1977, as a Valdez City Council member, Walker traveled with a delegation from the Organization for the Management of Alaska Resources to meet with California Gov. Jerry Brown. (Photo courtesy of Bill and Donna Walker)

The announcement this summer that Alaska will pursue a state-owned natural gas pipeline is a major U-turn after more than a decade of negotiations with the big three North Slope oil companies.

But one person has been advocating this approach all along: Bill Walker.

For years, Walker argued the state should take control of the project, instead of putting its faith in the industry.

Then, he became governor.

This week, Alaska’s Energy Desk is exploring the the state’s 40-year quest for a natural gas pipeline in the series Pipeline Promises.

Today, we look at Gov. Bill Walker’s decades-long mission to build a gas line.

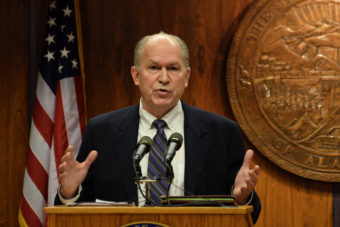

About a year ago, Gov. Bill Walker stood before reporters, addressing his most recent dust-up with the state’s oil companies.

In a moment of exasperation, he said, look. This is about Alaska’s future.

“It has to do with controlling our destiny, and not allowing somebody else to control our destiny,” he said in a press conference before the legislature’s special session on the gas line. “I stand firm on that principle.”

This is the heart of the Bill Walker philosophy: this gas line, this “piece of pipe,” as he calls it, is central to Alaska’s destiny, and it is never going to get built unless the state takes charge. We simply cannot leave it to the oil companies, he argued.

Now, Alaska has a chance to test that theory.

For the man in the driver’s seat, the seeds of this philosophy were planted almost fifty years ago, with the state’s other pipeline – the oil pipeline.

“I graduated from high school in ’69 in Valdez, and I could not afford to go to college,” Walker said in a recent interview. “I mean, there was no way I could afford to go to college.”

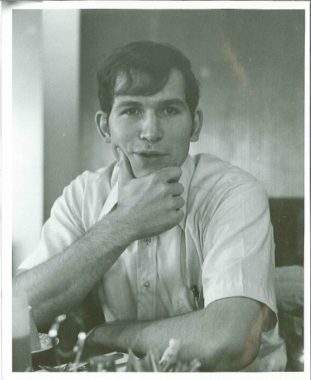

Bill Walker during college. (Photo courtesy of Bill and Donna Walker)

What saved him, he said, was early work on the trans-Alaska pipeline. He still remembers getting his dispatch – the piece of paper calling him up for a job on the project.

“I’ve gotten a number of degrees in my life, and I can’t tell you a single name of the person that gave me [them],” he said. “But I can tell you the name of the person who gave me that dispatch. His name was Jim Robinson, it was at the Johnson Trailer Court in Valdez, and I stood there with a couple of my buddies, and I thought, ‘This is my ticket, for my future.’”

Walker says what the last pipeline meant to him, the next line could mean for a whole new generation. Jobs, of course. Revenue for the state. Cheap energy that could launch whole new industries. New incentive for companies to explore the North Slope.

His first encounter with the gas line came a few years after that moment in the Valdez trailer court. Walker was in his mid-20s. He’d just met his wife, and he was serving on the Valdez City Council.

“And the mayor said, ‘who wants to work on the gas line?’” Walker said. “I said, ‘well, I’ll work on the gas line. I worked on the oil line, so I’m happy to work on the gas line.’”

He ended up traveling to California to meet with then- (and now-) Gov. Jerry Brown to advocate for an Alaska LNG line to ship gas to the West Coast. That version of the project, like so many after it, fizzled. But Walker stayed involved in oil and gas — and often found himself at odds with the state’s dominant industry.

In the late 1990s, the gas line came back into his life. He was called to a meeting of mayors from the North Slope, Fairbanks and Valdez. They had formed a group called “Gasline Now!”

“[They said], what can we do to add a few more percentage of return to the gas line, so the producers would build a gas line?” Walker said.

The idea was to jump-start a project by using the local governments’ tax-exempt status to try to tempt the oil companies to the table. The result was the Alaska Gasline Port Authority (AGPA).

Then-Valdez Mayor Bill Walker congratulates Alyeska’s Marine Terminal manager on the arrival of the one billionth barrel of oil, 1979. (Photo courtesy of Bill and Donna Walker)

Walker ended up working with the Port Authority for more than a decade, trying to advance what he called an All-Alaska Gasline. (During this time, he also represented the City of Valdez in a long-running court battle with the North Slope producers, arguing the companies had undervalued the trans-Alaska pipeline in order to pay lower property taxes.)

Craig Richards went to work for Walker as a 27-year-old lawyer in the early 2000s. He went on to become Walker’s law partner, confidant and ultimately his first attorney general.

“Bill wasn’t doing academic papers. Bill was doing the real deal, he was meeting with Fortune 500 companies, and having real meetings about ways to monetize the gas. It was just very enticing,” Richards recalled.

He said the Port Authority years taught Walker several things. There were moments when Walker thought he’d pulled it off. He brought in big outside companies, like the California utility Sempra Energy, or Mitsubishi, who were interested in a project. They’d reach out to the North Slope companies who controlled the gas.

But, Richards said, “Phone never rang. Dead silence.”

“The answer of course, is that producers weren’t interested at that stage in making a pipeline happen,” Richards said. “They were interested in accomplishing other goals.”

Goals like using gas line negotiations with the state to lock in their oil and gas taxes and a friendly regulatory regime, Richards said.

Critics say the Port Authority never put together enough of a project to merit a real response.

But Richards said for him and Walker, the lessons were clear: The oil companies have their own priorities and their own timeline. If the state wants a gas line, it can’t wait for the companies to lead the way.

“One, he decided that he needed to be governor, if he was going to really see the gas line go to the next phase. And that was the beginning of his political ambitions,” Richards said. “And two, he realized it’s gotta be the state of Alaska that does this. At least in terms of the pre-development work.”

In 2010, Walker ran against then-governor Sean Parnell in the Republican primary, with the gas line as his main issue. An ad from that era features Walker speaking to the camera: “Folks ask me if I’m a one-issue candidate, and I’ll admit and it’s certainly no secret, I am committed to Alaskans building an all-Alaska gas line,” he says.

He lost that year, but ran again in 2014, as an independent. By then, Parnell and Republican lawmakers were advancing a new plan, a partnership with the big three North Slope producers – ExxonMobil, BP and ConocoPhillips – as well as the pipeline company TransCanada: the Alaska LNG project.

Bill Walker was not a fan.

“The fatal flaw of what [Parnell] is doing is, again, again, he has put control of Alaska’s future in the hands of companies that have competing projects around the world,” hetold KTVA’s Rhonda McBride in an interview in May 2014.

Gov. Bill Walker at a press conference Feb. 19, 2015. (Photo by Skip Gray/360 North)

Then, the unexpected happened: Walker won the election.

Former Anchorage Daily News reporter Bill White has researched the history of the gas line. I asked him if Walker’s single-minded pursuit of a state-owned project is his white whale – his Moby Dick. White: It’s his big obsession, for sure. Remains to be seen if it’s his white whale.

Alaska’s Energy Desk: Why?

White: Well, maybe he’s right. I wouldn’t bet on it, but maybe he’s right.

Now, Walker has a chance to prove it.

When he took office, oil and gas prices were plunging. Suddenly Alaska faced a massive revenue shortfall, and Walker was more convinced than ever that a gas line is the solution.

Low prices also created an opening, changing the dynamics of the Alaska LNG project Walker had inherited from Parnell.

On February 9, 2016, the state’s three oil-company partners sat down with Walker’s team.

“It was a day I’ll never forget,” Walker said.

According to both the governor and ExxonMobil, the companies told him that lousy market conditions and slow negotiations with the state meant they probably couldn’t move the project ahead as planned.

They proposed either slowing down or letting the state take over.

For Walker, this was his moment. And he seized it.

“I thought, my goodness. How long have we waited for this opportunity,” he said. Within months, his administration had announced it would pursue a state-owned project.

For many Alaskans, news that the big three oil companies have stepped back from the project is a sign the state’s gas line dream has hit another wall. But Walker doesn’t see it that way.

“We have proved over the last forty years what won’t work,” he said. “This is the first time we’ve said, let’s try it, one time, like other sovereigns do around the world.”

It’s not a wall, he said. “It’s a starting gate.”

VI. The man with the plan: Can Keith Meyer sell the gas line?

The man in charge is Keith Meyer, the new president of the Alaska Gasline Development Corp.

This week, Alaska’s Energy Desk is digging into the gas line project in the series, Pipeline Promises.

Today, Rachel Waldholz introduces us to the man with the plan.

Keith Meyer took over as the new president of the Alaska Gasline Development Corp. in June 2016. (Photo courtesy of AGDC)

To hear Keith Meyer tell it, this gas line project should not be that hard.

Back in June, when Meyer was about two weeks into his new job, he was called up to testify before lawmakers. And he said it’s always puzzled him that Alaska’s gas line has had so much trouble getting off the ground.

“Yes, it’s a big project,” he said. “[But] it’s not the biggest pipeline, it’s not the highest pipeline, it’s not the largest diameter pipeline, it’s not the largest LNG plant.”

It’s not an engineering problem at all, he said. “This project, I think, where it suffers, is not technical complexity. It’s the paperwork.”

That’s right. The project that’s eluded the state and some of the world’s largest oil companies for some four decades? It’s a paperwork problem.

That take left many people wondering – who is this guy?

“I consider myself a gas guy,” Meyer said, in an interview at AGDC’s offices just after he was hired.

Meyer has a vaguely 1950’s vibe: salt and pepper hair, hipster glasses. He says things like,neat and by golly.

He’s worked on pipeline and natural gas projects for more than 35 years, and said he’s known about Alaska’s project since the very first day of his career, back in 1980.

“And I remember at that time thinking, as a young buck in the industry, wow, that is a neat project,” he said. “You know, someday I might get to work on a project like that…So I was thrilled at the opportunity to be the one to bring it home.”

Meyer comes across as supremely confident he can bring it home.

But he inherited a project in flux. Earlier this year, Alaska’s three partners – ExxonMobil, BP and ConocoPhillips – told the state they likely wouldn’t move the project forward on the expected timeline.

The state decided to take over – which puts Meyer, and AGDC, in charge.

His first challenge is tackling the project’s Achilles heel: its price tag.

“Right now it’s high cost,” he told the Legislature in June. “So now our focus has to be on how do we get the cost reduction. How do we get the cost down?”

Meyer’s answer: re-imagining the project’s financing.

The existing project structure is pretty simple. The state is in a four-way partnership with the oil companies. Each party puts up their $10 to $15 billion – and voila! Project financed.

But with our partners headed for the exits, how does Alaska finance the project on its own?

Meyer said – we don’t have to.

He wants the state to quit acting like a deep-pocketed oil major and start acting like a scrappy pipeline company. You don’t pay for the project yourself. You bring in outside investors. You put together a deal. That’s what he means by “paperwork.”

“This is significantly different than the way it was done [to date],” he said. “However, it’s very similar to the way most of the pipelines in the US have been built and also the way most of the LNG facilities now have been built.”

Gov. Bill Walker has ruled out dipping into the Permanent Fund, the state’s $54 billion piggy bank. Meyer said the project also wouldn’t rely on general obligation bonds — the state’s everyday credit card, used for expenses like highway projects.

Instead, the state would rely on project financing. Essentially, AGDC will go out and try to secure customers — perhaps utilities in Japan that want to buy gas, or the North Slope producers themselves, who would pay to ship their gas down the pipeline. If the state can lock down long-term contracts, it can take those contracts to the bank — or, more likely, to private equity firms — using the contracts as the foundation to secure loans or investors for the first stage of the project. Once construction is underway, Meyer said, other third-party investors might want a piece of it, such as pension funds, insurance companies, infrastructure investors.

If that sounds pretty complicated — well, it is. But Meyer has some experience in this.

His calling card in the natural gas world is his work on Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass import terminal in Louisiana in the mid-2000’s.

“Keith played a huge role in one of the more important players in this remarkable period for energy,” said Wall Street Journal reporter Gregory Zuckerman, who wrote about Cheniere Energy in his 2013 book, The Frackers. “He was part of this effort to import natural gas when it seemed like the country needed it.”

Cheniere Energy managed to do pretty much what Meyer is proposing in Alaska: it didn’t own any gas, it didn’t have deep pockets, but it locked in contracts with big companies that wanted space in its terminal and used those contracts to go out and get financing to build the project.

Zuckerman said Meyer gets part of the credit for that, for promoting the project and making the case to investors.

“He was among the people that concluded some of the best agreements and contracts for Cheniere, according to people close to the matter. So he would be a good person to pull that off,” Zuckerman said. “The challenge, obviously, is that these are really expensive projects. And the energy business, as we’ve learned over the last few years, can change dramatically.”

That’s what happened to Cheniere. The Sabine Pass project was put together in the mid-2000’s, when the U.S. thought it was facing an energy shortage. Then the fracking boom swamped the gas market. Cheniere’s value plunged. The company only saved itself by turning its import project into an export project. By then, Meyer had left the company.

There are major differences between the projects. LNG import projects are by definition simpler and cheaper than export projects. And the Sabine Pass import project was also much smaller than Alaska’s project – something like the difference between financing a Kia and a Tesla.

I asked Meyer if he had ever put together project financing for something the size of the Alaska LNG project, which is estimated to cost at least $45 billion.

“No one has,” he said.

In other words, financing the project as it currently exists would be unprecedented.

Meyer’s goal, of course, is to keep the project well below $45 billion, through a combination of cheaper financing, the potential tax benefits of state ownership, and, perhaps, building it in multiple phases.

But he said he’s under no illusions about the challenges. Alaska’s project is big. It’s expensive. He’s confident there’s a growing market for natural gas, but there are a lot of LNG projects competing to fill that demand.

But, he said, if Alaska waits, the competition will only get worse.

“We’re fighting with some of the biggest companies in the world, some big countries,” he said. “And, by golly, we’ve got to get out there and fight for this Alaskan project.”

PART V: Questions surround Walker’s gas line plan

Gov. Bill Walker is making the case that his new gas line plan will get the project off the drawing board and on to Alaskan soil. But it’s not hard to find skeptics who say Walker is just creating more paperwork.

As a new energy reporter in Alaska, it didn’t take long for me to notice that even though state leaders are always talking about the gas line, there’s something left unsaid. I mentioned this to Larry Persily, a gas line expert who now advises the Kenai Peninsula Borough.

HARBALL: It seemed to be this unstated truth that a lot of people don’t believe this is going to happen. This may not even materialize…

PERSILY: Right, oh yes. Even a couple years ago when [Alaska LNG] looked like, hey! People were still like, ‘Oh, it won’t happen.”

HARBALL: Right, and being a new Alaskan…

PERSILY: Do you have a dog yet?

No dog yet. That being said, this new Alaskan had to learn why so many people think the governor’s plan is doomed.

Skeptics like Persily see big forces working against the project.

The biggest is the market: this is an expensive project aimed at supplying a product, gas, that today is plentiful and cheap.

“Prices for the commodity are down, the project is one of the most expensive energy projects ever in the history of the world, so that alone would make a lot of people skeptical,” said Persily. “They look at the price tag, look at what you are going to get for the project at the end and they say, ‘that’s not going to happen, turn the TV back on.’”

Lousy market conditions help explain why the big oil companies are stepping back from the effort to build the gas line. And this plays into another big issue skeptics bring up — one that became clear as I walked into Anchorage Republican State Senator Cathy Giessel’s office. We spoke sitting between stacks of cardboard boxes. Oil-dependent Alaska can’t afford the legislature’s sleek new building, so lawmakers are moving.

The governor argues Alaska’s dire fiscal situation is one reason to charge ahead. Giessel said it’s a reason to be cautious.

As much as she’s like to see the project built, she said, “We have a significant budget challenge right now and I think that we can overplay our hand and find ourselves in an even worse fiscal predicament if we act rashly.”

Giessel said she’s not sure the state has the capacity to manage the project and she’s not sure how much it’s going to cost to build that capacity. She also said more state control means the state is taking on more responsibility for the project’s risks, as well.

This idea of risk brings us to the other reasons people are skeptical, which have to do with Walker’s plan in particular. That plan, in brief, is for the state to bring in money from outside investors rather than relying on the oil companies to pay for most of the gas line. State leadership may also mean some part of the project may not have to pay federal taxes. In late August, energy analyst David Barrowman of Wood Mackenzie told lawmakers that in theory, elements of Walker’s proposal could be a promising way to bring the project’s total cost down.

“Currently Alaska LNG, in terms of global competitiveness, is quite challenged,” Barrowman said. “But there are levers that can be used.”

Those levers, he said, are exactly the ones Walker is trying to pull to reduce the project’s price tag — attracting third party investors and avoiding some federal taxes. But the next day, the legislature’s energy consultant, Nikos Tsafos, took his turn before lawmakers and tore into Walker’s plan.

“You usually want to take over economic projects, not uneconomic projects,” Tsafos said.

One of Tsafos’ critiques is the idea of outside investors. The oil companies — BP, ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips — worry their investments in a gas line wouldn’t pay a high enough return to be worthwhile. The governor argues that instead, the state can find outside investors, like pension funds, that would require less of a profit on the project and finance it more cheaply.

In an interview, Tsafos said he’s not sure investors like this actually exist.

“I mean borrowing money — everyone borrows money,” Tsafos said. “The idea that somehow the state of Alaska has discovered that by borrowing money the project could be made cheaper, that doesn’t make any sense, right?”

Tsafos said he’s looked at other projects around the world and can’t find many examples of the kind of investors the governor has in mind backing LNG projects, much less at this massive scale and this early in the game. And Tsafos doubts they’ll accept less profit in return for their investment than the oil companies.

Walker also wants to make the pipeline cheaper by getting out from under some federal taxes. A lot of the state of Alaska’s projects don’t pay federal taxes because they benefit the public. The governor argues if Alaska leads the way, it can make a case that part of the project won’t owe the IRS a check.

But Walker’s skeptics argue that because this project will involve private interests — potentially some of the wealthiest companies in the world — the IRS may not approve of this idea.

“This is not a school or a highway for general public use,” said Persily. “This is really a private undertaking where 95 percent of the gas is going to go not just outside of Alaska, but overseas.”

After hearing all this skepticism, I started to wonder: what’s the downside? What if the project doesn’t work? Will the state lose billions of dollars? Will I have to pack up my bags and move back to Washington, D.C.?

Everyone told me: calm down. Walker is taking one step in what’s going to be a very long journey. Will it cost money? Sure, and that’s important to pay attention to at a time when every dollar for the gas line is one that doesn’t go to other state services.

But Persily said it’s nothing compared to what the state has spent on this project in the past.

“Looking at the hundreds of millions the state has spent in the last 10 years, the billion the companies have spent in the last 10 years on this — if that’s what it takes to put this to rest…if that’s the political price of all this, maybe that’s the way we’ve got to go,” he said.

Persily gives Walker’s plan a 10, maybe 20 percent chance of working. But he’s not losing any sleep over it.

Meanwhile, Walker will spend the next year making a case to the public, lawmakers and the market in hopes of proving his skeptics wrong.

Leave A Comment